The previous chapter surveyed data models and established why structured, schema-enforced approaches are essential for scientific research. Among these, the relational model stands out for its mathematical rigor, powerful query capabilities, and proven track record. This chapter explores its theoretical foundations.

Origins of Relational Theory¶

Relations are a key concept in mathematics, representing how different elements from one set are connected to elements of another set. When two sets of elements are related to each other, this forms a second-order or binary relation. Higher orders are also possible: third, fourth, and order relations.

If you are conversant in Set Theory, then an order relation is formally defined as a subset of a Cartesian product of sets. Many useful operations can be modeled as operations on such relations.

Imagine two sets: one set representing clinics and another representing animal species. A relation between these two sets would indicate, for example, which clinics treat which species.

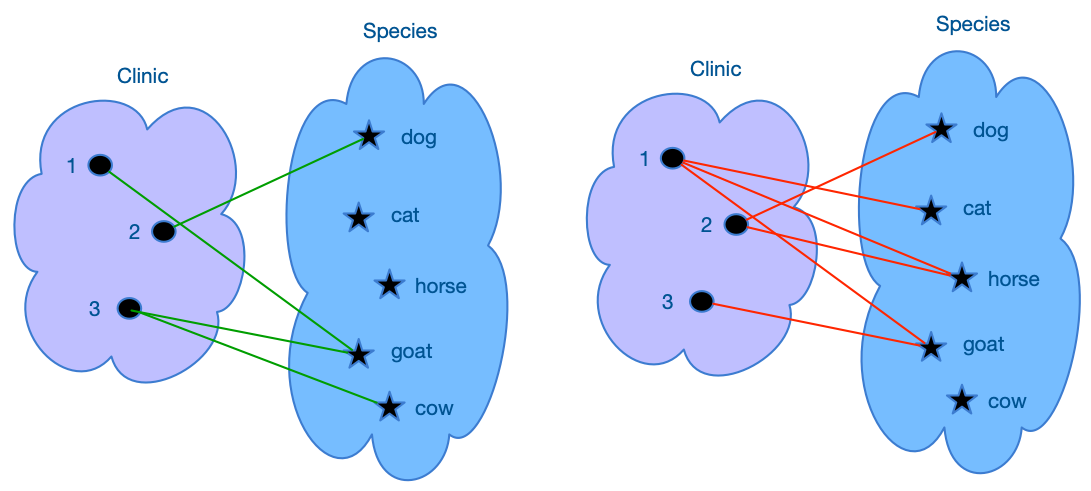

Figure 1:Relations are mappings of elements of one set to elements of another domain (binary relations). Higher order relations map elements of three, four and more sets.

This diagram illustrates two different relations between “Clinics” and “Species.” On the left side, the relation shows Clinic 1 is connected to “goat,” Clinic 2 is connected to “dog,” and Clinic 3 is connected to both “goat” and “cow.” On the right side, the relation changes: Clinic 1 is now connected to “dog,” “horse,” and “goat,” Clinic 2 is connected to “dog” and “horse,” and Clinic 3 is connected to “goat.”

Each line connecting elements of the two sets is called a tuple and represents an ordered pairing of values from the corresponding domains. Then a relation can be thought of as a set of tuples. The number of tuples in a relation is called its cardinality and the number of domains participating in the relation is its order. This diagram shows binary relations. Relations can be binary, ternary, or of higher orders.

Mathematically, a relation between two sets (e.g., clinics) and (e.g., species) is a subset of their Cartesian product . This means the relation is a collection of ordered pairs , where each is an element from set , and each is an element from set . In the context of the diagram, each pair represents a specific connection, such as (Clinic 1, Dog) or (Clinic 3, Cow).

These relations are not fixed and can change depending on the context or criteria, as shown by the two different values in the diagram. The flexibility and simplicity of relations make them a powerful tool for representing and analyzing connections in various domains.

The Historical Development of Relational Theory¶

The concept of relations has a rich history that dates back to the mid-19th century. The groundwork for relational theory was first laid by Augustus De Morgan, an English mathematician and logician, who introduced early ideas related to relations in his work on logic and algebra. De Morgan’s contributions were instrumental in setting the stage for the formalization of relations in mathematics.

Figure 2:Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) developed the original fundamental concepts of relational theory, including operations on relations.

The development of relational theory as a formal mathematical framework is largely credited to Georg Cantor, a German mathematician, in the late 19th century. Cantor is known as the father of set theory, which is the broader mathematical context in which relations are defined. His work provided a rigorous foundation for understanding how sets (collections of objects) interact with each other through relations.

Cantor’s set theory introduced the idea that relations could be seen as subsets of Cartesian products, where the Cartesian product of two sets and is the set of all possible ordered pairs where is from and is from . This formalization allowed for the systematic study of relations and their properties, leading to the development of modern mathematical logic, database theory, and many other fields.

Figure 3:Georg Cantor (1845-1918) reframed relations in the context of Set Theory

Building on this foundation, mathematicians in the early 20th century, including George Boole (Boolean algebra), continued to develop the logical frameworks that would eventually underpin computer science and database theory.

Mathematical Foundations¶

Relational theory is not just a mathematical curiosity; it is a powerful tool that underpins many important concepts in mathematics and computer science. The ability to describe and analyze how different objects are connected is fundamental to many areas of study.

One of the most important applications of relational theory is in the concept of functions. A function is a specific type of relation where each element in the domain (the first set) is associated with exactly one element in the codomain (the second set). Functions are essential in nearly every area of mathematics, from calculus to linear algebra.

Relational theory is a superset of graph theory, where relationships between objects can be visualized as graphs. A directed graph can be thought of as a binary relation between a set of vertices and the same set of vertices again. Each tuple in such relation represents an edge in the graph. Graph theory helps in understanding complex networks, such as social networks, computer networks, and even biological networks. Thus theorems discovered or proven in relational theory also apply to graphs.

Relational theory also extends to concepts like equivalence relations and order relations. Equivalence relations partition a set into disjoint subsets called equivalence classes, while order relations arrange elements in a sequence. These concepts are fundamental in areas such as algebra, topology, and analysis.

Relational theory has been shown to be deeply interconnected to first-order logic and predicate calculus at the foundations of mathematics and logic. Relational theory, which focuses on the study of relations between elements of sets, forms the basis for the predicates used in first-order logic and predicate calculus. In first-order logic, predicates represent relations, and the logical statements describe how these relations interact.

The equivalence between relational theory and first-order logic was notably formalized by Alfred Tarski in the 1930s. Tarski demonstrated that every relation can be described by a formula in first-order logic, establishing a profound connection between these mathematical frameworks that has since underpinned much of modern theoretical computer science and logic.

Mathematical Rigor: Engineering Principles for Data¶

It’s crucial to understand that structured data approaches embodied by the relational model did not arise from corporate rigidity or bureaucratic necessity. They emerged from mathematical rigor and the desire for expressive, provable ways to manage data.

The intellectual foundations trace back to the 19th-century works of mathematicians like De Morgan, Boole, and Cantor, who formalized logic and set theory. These mathematical tools provided the bedrock upon which the relational data model was later built.

From Mathematics to Database Theory¶

Formalized by Edgar F. Codd in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the relational model was a direct application of these mathematical concepts—specifically Set Theory and predicate logic—to data management.

It’s like using precise engineering principles—physics, material science, geometry—to design a bridge, ensuring its stability, load capacity, and longevity based on provable calculations, rather than just nailing boards together based on intuition.

Before the relational model, dominant approaches like hierarchical and network models organized data in tree-like or graph-like structures, often embedding relationships directly within the data records. While functional, these models could be complex to query and lacked a strong theoretical foundation for ensuring data independence and integrity.

Codd’s insight was to represent data purely in terms of mathematical “relations” (visualized as tables), where relationships between data are expressed through shared values (keys) rather than physical pointers. This approach provided a clear, declarative way to define data structures (schemas), enforce constraints (like data types and uniqueness), and query data using logical operations.

The goal was precision, consistency, and a formal basis for data manipulation, not arbitrary inflexibility. The “rigidity” of schemas is actually mathematical rigor that enables provable properties and guarantees.

Three Levels of Abstraction¶

The evolution of relational database thinking provides three complementary levels of abstraction, each serving a distinct purpose:

1. Mathematical Foundation (Codd, 1970): Relations as mathematical sets, functional dependencies, normal forms. This provides the theoretical foundation and proves properties about what’s possible and optimal.

Like physics equations that govern how bridges must behave.

Codd’s relational algebra and calculus provide formal operations on relations with provable properties. Query optimization relies on these mathematical foundations to prove that two different queries produce equivalent results, allowing the system to choose the most efficient implementation.

2. Conceptual Modeling (Chen, 1976): Building upon Codd’s foundation, Peter Chen introduced the Entity-Relationship Model (ERM). While Codd’s model provided the rigorous mathematical underpinnings, Chen’s ERM offered a more intuitive, conceptual way to think about and design databases, particularly during initial planning stages.

Like architectural blueprints that translate engineering principles into buildable structures.

The ERM focuses on identifying key “entities” (things we store data about, like ‘Customers’ or ‘Products’) and the “relationships” between them (how entities connect, like a ‘Customer’ places an ‘Order’). Chen introduced Entity-Relationship Diagrams (ERDs) as a standard graphical way to visualize these entities, their attributes, and their relationships, serving as blueprints before database implementation.

This conceptual modeling step helps ensure the database structure accurately reflects the real-world scenario it represents, bridging the gap between business requirements and the logical structure of the relational model.

3. Implementation Language (SQL): The practical language for defining schemas and querying data. This is what you actually use day-to-day, but it’s built on the mathematical foundations that make it powerful.

Like the construction techniques and materials that realize the architectural design.

It’s vital to distinguish these layers. The relational model (Codd’s mathematical theory) and ERM (Chen’s conceptual modeling approach) are distinct from SQL (the implementation language). SQL is the most common language used to define, manipulate, and query relational databases, but SQL itself is not the model—the relational model and ERM provide the underlying principles.

Why This Matters for Science¶

This mathematical foundation isn’t just academic—it provides practical benefits that science desperately needs:

Provable Properties: Query optimizers can prove that two different queries are equivalent, choosing the fastest implementation automatically. This is only possible because of the mathematical foundations. When you write:

SELECT * FROM Neuron WHERE spike_rate > 10The optimizer might rewrite this in dozens of different ways (different join orders, index strategies, etc.) and prove they all produce identical results, then pick the fastest approach—all automatically.

Formal Guarantees: Constraints like foreign keys provide mathematically guaranteed integrity. The database can prove that your data relationships remain valid, not just hope they do. This isn’t wishful thinking or best practices—it’s mathematical certainty enforced by the system.

Declarative Expression: You specify what you want (declaratively) rather than how to get it (procedurally). This maps naturally to scientific questions: “Show me all neurons with firing rate > 10Hz” rather than writing loops and conditionals. The system figures out the most efficient how, freeing you to think about the what.

Principled Evolution: Schema changes can be reasoned about formally. You can prove that a migration preserves data semantics or identify what must change. Database theory provides rules (normal forms) that guide schema design toward maintainable structures.

Compositional Queries: Because relational algebra is algebraically closed (operations on relations produce relations), you can compose complex queries from simple parts. Each step remains a valid relation, enabling step-by-step construction and verification of sophisticated analyses.

The next sections show how this mathematical rigor translates into practical database operations and query capabilities.

Relational Algebra and Calculus¶

Relational algebra is a set of operations that can be used to transform relations in a formal way. It provides the foundation for querying relational databases, allowing us to combine, modify, and retrieve data stored in tables (relations).

Examples of relational operators:

Selection (σ): Selects tuples from a relation that satisfy a given condition.

Projection (π): Selects specific attributes from a relation.

Union (∪): Combines the tuples from two relations into a single relation.

Set Difference (−): Returns the tuples that are in one relation but not in another.

Cartesian Product (×): Combines every tuple from one relation with every tuple from another.

Rename (ρ): Renames the attributes of a relation.

Join (⋈): Combines related tuples from two relations based on a common attribute.

Such operators together represent an algebra: ways to transform relations into other relations. Some operators are binary, i.e. they accept two relations as inputs to produce another relation as output.

The operators are algebraically closed, i.e. the operators take relations as inputs and produce relations as outputs. This means elementary operators can be combined in sophisticated ways to compose complex expressions. Algebraic closure is an important concept behind the expressive power of relational operators.

To illustrate a relational operator, let’s consider the union operator (∪) using the two relational values from the diagram. The union of these two relations would combine all the connections from both diagrams into a single relation.

In the first value (left side of the diagram), we have the following connections:

Clinic 1 → Dog

Clinic 2 → Horse

Clinic 3 → Goat, Cow

In the second value (right side of the diagram), the connections are:

Clinic 1 → Dog, Cat, Goat

Clinic 2 → Dog, Horse

Clinic 3 → Goat

The union of these two relations would include all the connections:

Clinic 1 → Dog, Cat, Goat

Clinic 2 → Dog, Horse

Clinic 3 → Goat, Cow

This operation effectively merges the connections from both sets of values, providing a comprehensive view of all possible relations between clinics and species.

Relational algebra, with its powerful operators, allows us to query and manipulate data in a structured and efficient way, forming the backbone of modern database systems. By understanding and applying these operators, we can perform complex data analysis and retrieval tasks with precision and clarity.

Another formal language for deriving new relations from scratch or from other relations is relational calculus. Rather than using relational operators, it relies on a set-building notation to generate relations.

Relational Database Model¶

The relational data model is the brainchild of the British-American mathematician and engineer Edgar F. Codd, earning him the prestigious Turing Award in 1981.

Working at IBM, Codd explored the possibility of translating the mathematical rigor of relational theory into a powerful system for large-scale data management and operation Codd, 1970.

Figure 4:Edgar F. Codd (1923-2003) revolutionized database theory and practice by translating the mathematical theory of relations to data management and operations.

Codd’s model was derived from relational theory but differed sufficiently in its basic definitions to give birth to a new type of algebra. The relational data model gave mathematicians a rigorous theory for optimizing data organization and storage and to construct queries.

Through the 1970s, before relational databases became practical, theorists derived fundamental rules for rigorous data organization and queries from first principles using mathematical proofs and derivations. For this reason, early work on relational databases has an abstract academic feel to it with rather simple toy examples: the ubiquitous employees/departments, products/orders, and students/courses.

The design principles were defined through the rigorous but rather abstract principles, the normal forms Kent, 1983. These normal forms provide mathematically precise rules for organizing data to minimize redundancy and maintain integrity.

The relational data model is one of the most powerful and precise ways to store and manage structured data. At its core, this model organizes all data into tables—representing mathematical relations—where each table consists of rows (representing mathematical tuples) and columns (often called attributes).

The relational model is built on several key principles:

Data Representation: All data is represented in the form of simple tables, with each table having a unique name and a well-defined structure.

Domain Constraints: Each column in a table is associated with a specific domain (or datatype, a set of possible values), ensuring that the data entered is valid.

Uniqueness Constraints: Ensure that each row in a table is unique, enforced through a primary key.

Referential Constraints: Ensure that relationships between tables remain consistent, enforced through foreign keys.

Declarative Queries: The model allows users to write queries that specify what data they want rather than how the database will retrieve it.

The most common way to interact with relational databases is through the Structured Query Language (SQL). SQL is a language specifically designed to define, manipulate, and query data within relational databases. It includes sublanguages for defining data structure, manipulating data, and querying data.

When speaking with database programmers and computer scientists, you will often run into different terminologies. Practical database programmers speak of tables and rows while theoretical data modelers may describe the same things as relations and tuples.

The difference in terminology used in relational theory and relational databases.

| Relational Theory | Database Programming & SQL | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Relation | Table | A set of tuples that share the same attributes from each of the domains in the relation. |

| Domain | Data Type | The set of permissible values that an attribute can take in any tuple of a relation. |

| Attribute | Column | The positional values in the tuples of relation drawn from their corresponding domain. |

| Attribute value | Field | The positional value in a specific tuple. |

| Tuple | Record or Row | A single element of a relation, containing a value for each attribute. |

Why Relational Databases for Science?¶

The mathematical rigor of relational theory might seem abstract, but it provides precisely what scientific research needs: a formal framework for ensuring data integrity and enabling complex queries.

The Scientific Case for Relational Databases¶

Data Integrity Through Constraints: Referential integrity prevents orphaned data and inconsistent relationships—critical when each data point represents hours of expensive experiments or computation. Foreign keys ensure that relationships between entities remain valid, primary keys guarantee uniqueness, and data type constraints prevent invalid values from entering the system.

Think of integrity constraints as quality control checks that happen automatically, constantly, for every data operation. Unlike metadata-based approaches where integrity relies on everyone following conventions, schema-enforced integrity is guaranteed by the system.

Declarative Queries: SQL’s declarative nature means you specify what you want, not how to get it. This maps naturally to scientific questions: “Show me all neurons with firing rate > 10Hz” rather than writing loops and conditionals. The database optimizer determines the most efficient execution plan, freeing you to focus on your scientific questions rather than implementation details.

Mathematical Foundation Enables Optimization: Query optimizers can automatically find efficient execution plans because the mathematical properties of relational algebra enable formal reasoning about query equivalence. Two queries that ask for the same data can be proven mathematically equivalent, allowing the system to choose the fastest approach. This optimization happens automatically, without requiring you to understand the underlying algorithms.

Structured Flexibility: Schemas can evolve as your understanding grows. Unlike rigid file formats, databases allow controlled schema evolution while maintaining integrity. You can add new tables, modify existing structures, and migrate data systematically. The schema serves as documentation of your data structure, making it easier for collaborators to understand and contribute to your work.

Importantly, schema evolution in relational databases is a well-studied problem with established best practices (migrations, versioning, backward compatibility). This is very different from unstructured formats where evolution often means creating incompatible file versions.

Concurrent Access and Consistency: Multiple researchers can work with the same data simultaneously without conflicts. The database ensures that everyone sees a consistent view of the data, handles concurrent updates safely through transactions, and prevents race conditions that could corrupt your results.

Scalability: Relational databases can handle datasets from megabytes to petabytes. As your research grows, the database scales with you, maintaining performance through indexing, query optimization, and efficient storage management.

From Theory to Practice: The DataJoint Extension¶

Traditional relational databases excel at storage and retrieval but weren’t designed for the computational workflows central to research. They can’t express:

“This result was computed FROM this input”: Foreign keys establish relationships but don’t capture computational dependencies. The database knows NeuralUnit references Recording but doesn’t understand that spike rates are derived from the recording data through a specific computation.

“Recompute everything downstream when inputs change”: When you correct an error in source data, the database won’t automatically identify and recompute dependent results. You must manually track dependencies and orchestrate recomputation. There’s no distinction between “data changed because someone edited it” and “data changed because upstream inputs changed.”

“Run this analysis automatically on all new data”: There’s no mechanism for “when a new Recording appears, automatically compute NeuralUnits.” The database stores data; external scripts perform computations, requiring manual workflow coordination. This separation makes it easy for data and code to fall out of sync.

“Track how this result was computed”: Provenance—knowing which code version, parameters, and inputs produced a result—must be implemented separately if at all. The database doesn’t distinguish between manually entered data and computed results. Version control is external; parameter tracking is application logic; the connection between results and the exact code that produced them is maintained manually.

“Ensure computational validity”: You can UPDATE a computed result without recomputing it, silently breaking the connection between inputs and outputs. The database maintains referential integrity (no orphaned records) but not computational validity (results consistent with their sources). A foreign key prevents deleting inputs while outputs exist, but it doesn’t prevent modifying inputs while keeping stale outputs.

The Workflow-Aware Extension¶

This is where DataJoint enters. The next chapters show how DataJoint extends relational theory with workflow semantics—turning your database schema into an executable specification of your scientific pipeline while preserving all the benefits of relational rigor.

The key insight: Your database schema becomes your workflow specification. Tables represent workflow steps, foreign keys express computational dependencies, and the system ensures that results remain valid as data evolves. This transforms databases from passive storage systems into active workflow managers that understand the computational nature of scientific work.

DataJoint doesn’t abandon relational theory—it extends it. All of Codd’s mathematical foundations remain:

Relations as sets of tuples

Relational algebra operations

Referential integrity through foreign keys

Declarative queries

But DataJoint adds new layers:

Table tiers that distinguish manual, imported, and computed data

Computational dependencies captured in the schema

Automatic populate() operations that maintain workflow validity

Immutability as default preserving provenance

Schema as workflow specification making dependencies explicit

The result is a system with the mathematical rigor of relational databases plus the workflow awareness that scientific computing requires.

Exercises¶

Extend Relations: Extend the binary relation

Clinic-Speciesto a higher order, e.g. a ternary relation.

Join Relations: Imagine that you have two binary relations:

Clinic-SpeciesandSpecies-Treatment. How can these two binary relations be joined into a ternary relation:Clinic-Species-Treatment? What would the rules be for forming this result? What will be the cardinality (number of tuples) of the result?Project Relations: Imagine that we decide to remove the domain

Speciesfrom the relationClinic-Species-Treatment, producing a new binary relationClinic-Treatment. How will the number of tuples be affected? What would be the rules for this operation? How would the cardinality (number of elements) change in the result?Mathematical Foundation: Explain in your own words why the mathematical foundation of relational databases matters for scientific research. How does “mathematical rigor” translate into practical benefits?

Three Levels: Consider a database design problem from your field. How would you approach it at each of the three levels: (a) mathematical/logical structure, (b) conceptual ER model, (c) SQL implementation? What does each level contribute?

Workflow Gaps: Consider a scientific workflow you know well. Identify where traditional relational databases would help and where they would fall short:

What entities exist and how are they related?

What constraints would prevent invalid data?

What queries would you need to answer scientific questions?

Where would traditional relational databases struggle with your computational workflow?

- Codd, E. F. (1970). A relational model of data for large shared data banks. Communications of the ACM, 13(6), 377–387. 10.1145/362384.362685

- Kent, W. (1983). A simple guide to five normal forms in relational database theory. Communications of the ACM, 26(2), 120–125. 10.1145/358024.358054